Interview with

Dr. Sahib Khalsa

Dr. Sahib Khalsa, M.D., Ph.D.

Dr. Khalsa graduated from the Medical Scientist Training Program at the University of Iowa, receiving M.D. and Ph.D. (neuroscience) degrees. He is currently the Director of Clinical Operations at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research, and an Associate Professor of Community Medicine at the University of Tulsa. Dr. Khalsa’s research investigates the role of interoception in mental health, with a focus on understanding how changes in internal physiological states influence body perception and the functioning of the human nervous system. His studies utilize a variety of approaches to probe cardiovascular, respiratory, and gastrointestinal interoception including via pharmacological and non-pharmacological techniques, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), electroencephalography (EEG), and computational modeling.

Parts of the interview have been edited for clarity and length.

What is interoception and why is it important for health?

Interoception refers to the process by which the nervous system senses, interprets, and integrates information about the internal state of the body. It’s a process that spans multiple levels of functioning within the nervous system, which includes the peripheral nervous system (the autonomic and somatic branches) as well as the central nervous system. Interoception also bridges multiple physiological states. For example, there are many physiological signals which we are not aware of. For those signals which we are aware of, the degree to which we are aware or conscious of them is sometimes very meaningful, particularly in the context where homeostasis is disrupted and where the integrity of the body is threatened.

Interoception is important for physical and mental health because it is the primary way that we become aware of internal status of the body. For example, noticing your heart beating strongly in your chest might be called a palpitation. That could be indicative of potentially very serious medical condition like a heart attack or abnormal heart rhythm, so you can think of a major role of interoception is to act an early warning system. Noticing those symptoms could lead somebody to seek help and undergo and diagnostic evaluation, resulting in detection of this pathologic process in the body and, in ideal circumstances, lead to the appropriate treatment and resolution. Dyspnea or difficulty breathing during an asthma attack or pneumonia are other examples physical manifestations, that if left untreated, could have drastic consequences.

There are also a tremendous number of mental health conditions where the condition itself is diagnosed or characterized by abnormalities of interoception. Using the cardiac example, somebody might come to the Emergency Department complaining of heart palpitations. But at the end of the evaluation, the doctor says that they’re not having a heart attack and their cardiovascular system is intact. In this example, their symptoms might be better explained by a mental health condition such as panic disorder, where a person misinterprets the sensation of their heart beating faster as indicative of impending death. Appetite changes and fatigue in depression, autonomic hypervigilance in PTSD, abdominal fullness in eating disorders, and muscle tension in generalized anxiety disorder are some other examples.

What is interoceptive psychopathology and how would a specific intervention that targets interoceptive processing help?

It might be helpful to think of interoceptive psychopathology as the aspects of psychiatric illness or mental health that relate to abnormal processing of the body’s internal state. Interventions targeting the processing of interoceptive symptoms help to recalibrate the abnormal sensory experience. For example, interoceptive exposure therapy for panic disorder is a commonly employed intervention that helps people approach their feared internal body sensations, such as heart palpitations or dyspnea, and learn to avoid misinterpretations or abnormal expectations. No longer fearing or catastrophically misinterpreting body sensations allows people to experience their body and the world environment without hindrance and to ultimately experience a fuller life. While this is one example of a commonly used interoceptive intervention in current clinical practice, there are currently several others in various stages of development.

Why is a mixed method approach to science important to your work?

I include mixed method and multilevel approaches in my work because interoception is a process that covers multiple levels of processing and many types of experiences. It may not be completely understood by focusing on one aspect of an organ system as it interacts with the nervous system, or by focusing only on nervous system signaling. Mixed method approaches which incorporate subjective experiences allow me to develop an integrated understanding of how the processing of interoceptive signals impacts the entire organism, across different levels of awareness. That kind of approach is incredibly important for any type of science, but especially contemplative neuroscience research, where there are many different ways of obtaining insight into the impact of contemplative practices on the human experience.

Is mindfulness practice able to improve interoception?

This is a complex question because mindfulness is one component of a contemplative practice, and because there are many types of contemplative practices that have been investigated with respect to their ability to alter interoception. Most studies have utilized cross-sectional approaches that compare those with some degree of meditative or contemplative experience against those without. Studies looking at the interoceptive processing of the heartbeat in practitioners with various levels of contemplative experience have generally found that the accuracy of their ability to sense that signal is no greater than that of people who’ve never meditated. Some studies have also begun to look at the longitudinal impact when you take somebody without any established training and then you give them exposure to contemplative practice, whether it’s in mindfulness practice such as Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction or another practice that has roots in a contemplative or spiritual tradition. This allows us to see what happens with the person’s experience in processing interoceptive signals over time. There is some evidence for changes in the experience of interoceptive signals that happens with these practices, but to my knowledge it’s not the kind of change that most people would think is happening.

For example, you might be surprised to hear that contemplative practices are not strongly associated with increased accuracy of heartbeat perception. On the other hand, one important point is that accuracy of heartbeat perception is only one aspect of interoceptive awareness, even if it is the most studied process. You can also ask people how often they attend to those the internal body signal like the heartbeat, and you tend to find practitioners endorsing that they feel very familiar with it, that it’s an easy signal for them to perceive, and over time, their sense of that has improved. It would not be a fair statement to say that there is no impact on cardiac interoception.

You might also be thinking that it is more important to study awareness of the breath since that is a more common focus of sensory processing in many traditions. But it turns out that it’s been very difficult to derive methods for rigorously ascertaining the degree to which somebody can perceive their spontaneously arising respiratory signals. This is partly because of the voluntary regulatory influence that they can exert over this system. For example, try to convince me that your breathing pattern did not change after I told you not to hold your breath. One of the things that I noticed in my initial study of interoceptive awareness in experienced meditators was that as soon as we asked participants to pay attention to their heartbeat sensation, many of them started to change their breathing pattern. In some cases, they felt like it helped them to get into a more focused state of mind. In other cases, they felt like they were able to manipulate the signal of their heartbeat signal better therefore perform better in the task.

In the ensuing years since we did that study, there have been a number of clever ways to study respiratory interoception. One approach is where you directly manipulate the experience of the breath. You might potentially have somebody breathe through an apparatus and temporarily restrict the airflow as a way of simulating this state of dyspnea, or difficulty breathing. There’s still a lot of unexplored territory in this area and there’s considerable value to moving forward with more sophisticated methods and models. Overall, we need better ways of measuring interoception and more rigorously designed studies to conclusively answer this question.

“Mixed method approaches which incorporate subjective experiences allow me to develop an integrated understanding of how the processing of interoceptive signals impacts the entire organism, across different levels of awareness. That kind of approach is incredibly important for any type of science, but especially contemplative neuroscience research, where there are many different ways of obtaining insight into the impact of contemplative practices on the human experience.”

Your study found that meditation is not associated with enhanced interoceptive awareness, yet there have been previous reports of higher subjective ratings and meditators. What might explain this difference

Some of the discrepancies between studies in this area may have to do with different ways of assessing interoception, and also the fact that studies of cardiac interoception find that most people have a hard time feeling their heartbeat sensations under resting physiological conditions. But we all know what it feels like to experience our heartbeat sensation, and often that happens during periods of increased arousal, excitement, or physical activity.

Across two studies we found that meditators were not more accurately aware of their heartbeat signal than non-meditators. But we define interoceptive awareness as the entire process of consciously experiencing the internal state of your body, then it would necessarily span things like the ability to detect a sensation, to localize it to particular organ system, to discriminate it from another part of the body, to feel it with a certain level of or magnitude of intensity, in addition to a metacognitive experience of yourself proceeding through that feeling state.

In our most recent study, we used a pharmacologic stimulation with a medicine that acts peripherally to perturb heartbeat and breathing sensations. We did that in meditators, who had several years of Vipassana meditation experience relative to matched individuals who had did not have any meditation experience. We didn’t find clear evidence of differences in interoceptive accuracy, but we did see evidence that the meditators had a sizeable difference in how and where they experienced their heartbeat sensations in different parts of their bodies. There was also some preliminary evidence that perhaps they were more attentive to that signal.

Overall, in looking across multiple measures of cardiac interoceptive awareness we didn’t see the findings that we were predicting. I think what that leads to is a greater refinement of subsequent research questions.

“We didn’t find clear evidence of differences in interoceptive accuracy, but we did see evidence that the meditators had a sizeable difference in how and where they experienced their heartbeat sensations in different parts of their bodies. “

How can psychedelics enhance our understanding of the mind-body connection?

When you look at the impact that psychedelics have, it’s undeniable that there is a strong subjective experience that that they elicit. For some people, that’s incredibly powerful and positive and in others, it can be negative. The enthusiasm for investigating the role of psychedelic interventions for various mental health conditions is predicated on the notion that it’s possible to study them in a systematic and safe manner to achieve long-lasting clinical benefit.

In terms of how psychedelics might impact the mind-body connection, a common theme I’ve observed is that the onset of the psychoactive effect coincides with changes an interoceptive signals, like the heart rate, blood pressure, or breathing. That perturbation of the bodily state likely has an impact on neural activity in higher levels of the nervous system, but whether or not that’s tied to the psychedelic effect has not been examined. Certainly, you can posit that there’s an increased amount of internal bodily sensation that’s happening. For example, if you look at the subjective experience induced by MDMA (also known as ‘ecstasy’), there’s quite a lot of sensory signals from the skin that are acutely affected as part of the serotonergic effect. But there are other physiological aspects related to the pharmacological action of these drugs on the body. For example, nausea and vomiting can occur in some individuals following ingestion of psilocybin-containing mushrooms or ayahuasca.

More generally, if you look at how psychedelic interventions are currently delivered, a lot of them incorporate the attenuation of exteroceptive input the nervous system. For example, when people are experiencing the peak of the psychedelic effect, they might wear eyepatches or headphones to reduce or modify the visual and auditory signals received by the brain. One interpretation may be that blocking visual information from the outer world allows the images that are generated during the hallucinogen come to the forefront of the theater of consciousness without impedance by competing images. Whether that magnifies the effect or not I think is probably somewhat of an empirical question, but those are some of the thoughts that come to mind when I when I think of how psychedelics might alter the mind-body connection.

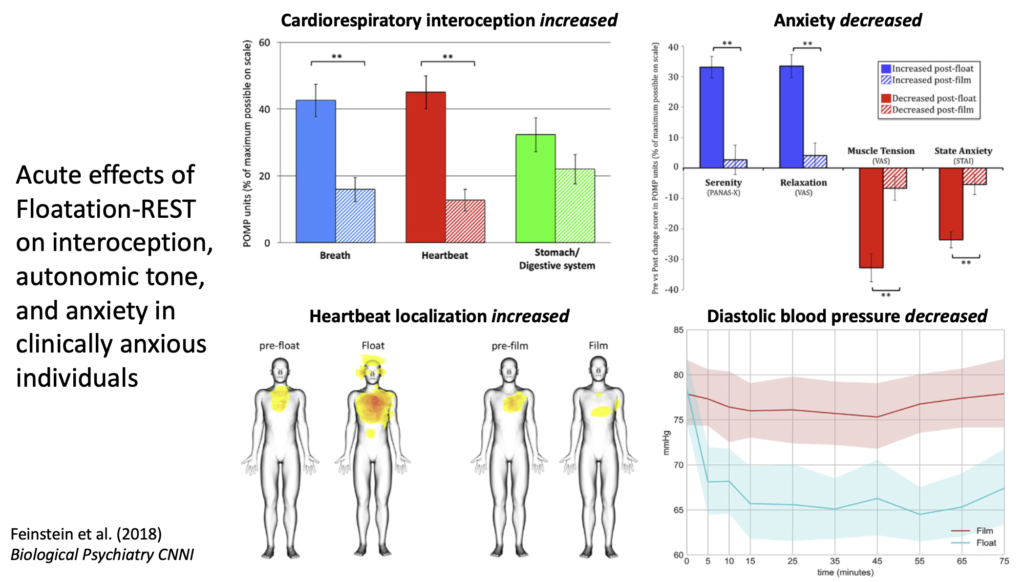

What is Floatation-REST and how does this expand our toolbox for clinical interventions?

Floatation-REST (Reduced Environmental Stimulation Therapy) is a non-pharmacological intervention that involves the systematic attenuation of certain kinds of exteroceptive signals to the nervous system, such as reducing visual and auditory input. It’s an intervention that’s delivered using sophisticated engineered environments involving a shallow pool of water that’s been hyper saturated with Epsom salts. When you lay down, your body floats effortlessly on the surface of the water and you don’t have to hold your breath or move your muscles to stay afloat. It’s also a thermally regulated environment where the air temperature and the water temperature are elevated and calibrated to reach the temperature of the surface of your skin. They’re also been colloquially called ‘float tanks’ (the older term is sensory deprivation). However, the intervention does not involve sensory deprivation but rather a form of sensory enhancement.

In our research studies with clinically anxious individuals, we’ve found that the float environment is incredibly stimulating. Both in terms of the intellectual and cognitive experiences that people have when they’re floating and in terms of the enhancement of interoceptive sensation. People routinely experience their heartbeats and their breathing sensations more intensely when they’re in the float environment relative to comparison conditions such as laying in a comfortable chair in a quiet and dimly lit room or watching soothing nature videos. But rather than feeling more anxious and panicked when feeling their heartbeat more intensely, they walk away from the experience feeling more relaxed.

Enjoy? Share with your friends

Michael Juberg

Michael is the Founder & Chief Editor of the Science of Mindfulness.

Related Posts

African American Mindfulness Researchers Make Vital Contributions

The growing recognition of transdisciplinarity’s powerful nature offers researchers valuable opportunities for collaboration

Moving Beyond the Headlines

Does the scientific content that we read always mean what it claims?

The Clark Unitive Effect: Bridging the ‘Valley of Death’ from Research to Practice

The growing recognition of transdisciplinarity’s powerful nature offers researchers valuable opportunities for collaboration

What is Mindfulness-based Resilience Training (MBRT)?

Also known as MBRT, this intervention helps first responders navigate their work more mindfully

Oppositional Cultural Practice®: OWN IT! FEEL IT! LIVE IT! LOVE IT!

Mindfulness practices like critical analysis can reveal the mental formations behind these tools.

Interview with Dr. Linda Carlson

Dr. Linda Carlson holds the Enbridge Research Chair in Psychosocial Oncology, is Full Professor in Psychosocial Oncology in the Department of Oncology, Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary, and Adjunct Professor in the Department of Psychology.

Mediating Mindfulness-Based Interventions with Virtual Reality in Non-Clinical Populations: The State-of-the-Art (Failla et al., 2022)

By providing an immersive, engrossing, and controlled visual and auditory experience in which participants can practice mindfulness techniques, Virtual Reality (VR) systems can create immersive, ecologically valid, first-person experiences that can even tap into physiological reactions that align with real-world experiences.

Trait Mindfulness and Relationship Satisfaction: The Role of Forgiveness Among Couples (Roberts et al., 2020)

The researchers were interested in understanding if forgiveness acts as a mechanism by which mindfulness relates to relationship satisfaction. They speculated that being mindful would allow individuals to be aware of their own and their partners’ emotions in a non-judgmental and non-reactive way. The increased awareness would make people more forgiving of partner transgressions, thereby enhancing relationship satisfaction.

Exploring the Nexus between Mindfulness, Gratitude and Wellbeing Among Youth with the Mediating Role of Hopefulness: A South Asian Perspective (Ali et al., 2022)

Emerging studies are highlighting the effectiveness of mindfulness, gratitude and hopefulness as positive psychological tools in helping people cope with anxiety and stress. These practices have also been considered beneficial in enhancing psychological health and well-being.

Interview with Dr. Christopher Germer

“…when mindfulness and self-compassion are in full bloom, they are nearly identical in a moment of suffering.”

What is Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC)?

Also known as MSC, this intervention teaches people to care for themselves as much as they care for others.

Interview with Dr. Steven Hickman

Self-compassion actually allows us to sustain our compassion for others because we’re being compassionate to ourselves as well.

Interview with Dr. Erin Bantum

My work, over the past fifteen years has had a core theme of social support running through it, and I’d like to create an online mindfulness meditation intervention that includes a group component, such that people who have experienced cancer can meet and practice mindfulness meditation together.

Interview with Dr. Amy Brown

I didn’t want them to needlessly struggle and suffer as much as I did, and mindfulness is one of those tools that definitely helps us all during this time. I’m helping them in the way that I wish I would have been helped.

Interview with Dr. Thao Le

Ultimately, my intention is for it to be a service space to help students, faculty, staff, or anyone from the community to connect with themselves. Don’t we all need to pause?

The challenges of bringing mindfulness into schools

After nearly three decades, a ban prohibiting public schools to offer yoga as an elective for grades K-12 has been overturned in Alabama.

Interview with Dr. Philippe Goldin

Philippe Goldin, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor at UC Davis and leads the Clinically Applied Affective Neuroscience Laboratory.

What is Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)?

Mindfulness-based stress reduction, also known as MBSR, is an 8-week evidence-based group program that teaches participants how to cope with their pain and stress using mindfulness meditation and Hatha yoga techniques.

What is Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT)?

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, also known as MBCT, is a group-based treatment program … developed to prevent relapse in clinical populations with recurrent major depressive disorder (MDD).

Interview with Blake Colaianne

Blake Colaianne is a former Earth science teacher turned contemplative researcher. He is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Human Development and Family Studies at Penn State University. His research focuses on supporting adolescent development using both a culture of belonging in high schools and prevention and promotion programs that teach mindfulness and compassion skills.

What is Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Teens (MBSR-T)?

The MBSR-T program (also known as the Stressed Teens program) was created in 2004 by Gina M. Biegel, MA, LMFT

What is Mindfulness?

Rather than proposing a single definition, mindfulness might be better understood in relation to the phenomenology of the various contemplative traditions and practices that intend to develop mindfulness.

What is the Present Moment? Some Warnings about Hanging out in it, and a New Scientific Theory of Meditation

Ruben Laukkonen is a cognitive neuroscientist at the VU University of Amsterdam. His research focuses on sudden insight experiences and the effects of intensive meditation on the mind and brain. Using a combination of neuroimaging, machine learning, and neuro-phenomenology, Ruben is investigating some of the most rare states of consciousness accessible to human beings. He has published articles in leading journals, given talks at prestigious conferences, and has written on topics that range from artificial intelligence to psychedelics. Ruben has an eclectic contemplative background, including different meditation traditions such as Zen, Advaita, and Theravada.

Interview with Michael Tumminia

Michael J. Tumminia is an avid meditator, researcher, and runner. He is currently a 3rd Year Applied Developmental Psychology PhD candidate at the University of Pittsburgh.

Your Brain is also Part of Your Body: Contextual and Contemplative Approaches in Physical Illness

Despite significant advances in the field of psychology due to increased research … the usual care of people with chronic medical conditions still often neglects the psychological issues associated with the physical dimension of the disease.

Interview with Dr. Juan Rios

“Whether you call it liberation, theology, transformative justice, mindfulness- we cannot separate those components of practice, all of those things are integrated. Integration brings peace, and peace within is key to embracing the other.”

An electrophysiological investigation on the emotion regulatory mechanisms of brief open monitoring meditation in novice non-meditators (Lin et al., 2020)

Despite growing knowledge that mindfulness meditation can enhance emotional wellbeing, very little is known about how it all works. How exactly does the act of meditation help us deal with the emotional rollercoaster of everyday life? Is mindfulness training actually “transferrable” to real world situations? What’s going on in the brain? Can we even measure it?

Interview with Grant Jones

Grant Jones (he/him) is an artist, contemplative, researcher, and activist. Currently, he is a 3rd Year Clinical Psychology PhD candidate at Harvard University and Co-Founder of The Black Lotus Collective.

The Power of Their Own Breath

“We focus on concentration,” Jones says. “So rather than sharpening your focus, which is what happens when you get anxious, the goal is to relax your focus.” The ability to utilize your breath to calm your nervous system is the first step to teaching mindfulness.

Self-compassion, quiet self, and the brain (Liu et al., 2020)

How does self-compassion protect depressed adolescents? Quieting the self may be the key.

When Less is More: Mindfulness Predicts Adaptive Affective Responding to Rejection via Reduced Prefrontal Recruitment (Martelli et al., 2018)

A study led by Alexandra Martelli investigated whether more mindful individuals (based on self-report measure scores) would respond to social rejection with less distress and if certain neurological mechanisms in the brain’s prefrontal cortex can potentially explain the role of mindfulness in reduced social distress.

Brief mindfulness session improves mood and increases salivary oxytocin in psychology students (Bellosta-Batalla et al., 2020)

A research team from Valencia, Spain recently investigated the effects of a brief mindfulness-based intervention on both mood and biological markers on a sample of health professional students.

Neurophysiological and behavioural markers of compassion (Kim et al., 2020)

A new study by Kim and colleagues explored how compassion-based training can affect two self-regulatory styles and its relationship to neural, physiological, and behavioral responses.

Interview with Dr. Ilana Nankin – Breathe For Change

Dr. Ilana Nankin—the Founder & CEO of Breathe For Change—is an award-winning entrepreneur, teacher educator, and former San Francisco pre-k teacher committed to using wellness as a vehicle for healing and social change.

Yoga and Mindfulness as a Tool for Influencing Affectivity, Anxiety, Mental Health, and Stress among Healthcare Workers: Results of a Single-Arm Clinical Trial (Torre et al., 2020)

Torre and colleagues recruited 70 HCWs from two hospitals in Rome, Italy for a 4-week course in yoga and mindfulness.

Mindfulness Buffers the Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak Information on Sleep Duration (Zheng et al., 2020)

A team of researchers based in the perceived epicenter of the virus, Wuhan, China, recently tested whether a brief mindfulness intervention delivered through an app could be effective for reducing anxiety and protecting nightly sleep during the unfolding pandemic.

Intrapsychic Correlates of Professional Quality of Life: Mindfulness, Empathy, and Emotional Separation. (Thomas & Otis, 2010).

Mindfulness practices can enhance a therapist’s ability to intentionally and flexibly regulate attention as well as emotional reactivity which has been demonstrated to influence burnout.

Interview with Dr. Helen Weng

Dr. Helen Weng is a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist who originally joined the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine in 2014 as a postdoctoral scholar in the Training in Research in Integrative Medicine (TRIM) fellowship. She is developing new ways to quantify meditation skills using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and machine learning to identify mental states of body awareness during meditation.

Physician Anxiety and Burnout: Symptom Correlates and a Prospective Pilot Study of App-Delivered Mindfulness Training (Roy et al., 2020)

A new study investigated whether a brief mindfulness training designed to reduce physician burnout could be delivered through a smartphone app.

Interview with Dr. Eric Garland

Dr. Eric Garland, PhD, LCSW is Presidential Scholar, Associate Dean for Research, and Professor in the University of Utah College of Social Work, Director of the Center on Mindfulness and Integrative Health Intervention Development (C-MIIND), and Associate Director of Integrative Medicine in Supportive Oncology and Survivorship at the Huntsman Cancer Institute.

Interview with Dr. David Vago

David Vago is Research Director of the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Interview with Dr. Jeff Brantley

Jeffrey Brantley, MD, is one of the founding faculty members of Duke Integrative Medicine, where he started the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program in 1998.

Role of Yoga and Mindfulness in Severe Mental Illnesses: A Narrative Review (Sathyanarayan et al., 2019)

The current study reviewed the wider scientific literature for the role of yoga and mindfulness interventions in the treatment of severe mental illness.

A Randomized Controlled Trial Examining the Effect of Mindfulness Meditation on Working Memory Capacity in Adolescents (Quach et al., 2015)

The amount of research involving mindfulness interventions has grown exponentially; however, only in the last decade has mindfulness research involving adolescents rapidly increased.

The Differential Moderating Roles of Self-Compassion and Mindfulness in Self-Stigma and Well-Being Among People Living with Mental Illness or HIV (Yang et al., 2016)

Mindfulness and self-compassion are theorized to disrupt the maladaptive repetition of negative thoughts and emotions for patients with chronic or mental illnesses, who are particularly susceptible to psychosocial distress.

The Emerging Trend of Mindfulness in Education

According to the Association for Mindfulness in Education, mindfulness can increase students’ emotional regulation, social skills, self-esteem, and organizational capacities.

Neural Stress Reactivity Relates to Smoking Outcomes and Differentiates Between Mindfulness and Cognitive Behavioral Treatment (Kober et al., 2016)

There is promising evidence that 70% of smokers would like to quit but less than 5% of unassisted attempts at quitting are actually successful.

Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention for Stimulant Dependent Adults: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial (Glasner et al., 2016)

In a recent pilot study by Suzette Glasner, Ph.D. and her team at the Integrated Substance Abuse Programs at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, they evaluated the effects of Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP) on reducing relapse susceptibility among stimulant-dependent adults receiving a contingency management (CM) intervention.

Long-term Mindfulness Training is Associated with Reliable Differences in Resting Respiration Rate (Wielgosz et al., 2016)

A major implication of the study suggests the distal effects of intensive retreat practice on respiration rates, a benefit not necessarily conferred by a brief, but full-day meditation session.

Examination of Broad Symptom Improvement Resulting From Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction in Breast Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Controlled Trial (Lengacher et al., 2016)

Researchers are exploring mindfulness-based interventions as a long-term treatment options to address the multitude of symptoms after cancer has been treated.

Epigenetic Clock Analysis in Long-term Meditators (Chaix et al., 2017)

While the scientific study of mindfulness has exponentially increased over the past few decades, only recently has the scientific community focused on the effects of meditation training on biological aging.